When people think of Karl Marx, they typically reduce his stance on religion to one infamous phrase, oft repeated but scarcely understood:

“Religion is the opium of the people. It is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of our soulless conditions.”

It’s a line that’s been endlessly quoted—and misquoted—over the years to characterize Marx - and Marxists - as egg-headed, pseudo-intellectual atheists with nothing but contempt for people of faith. And that isn’t without cause. After all, it’s the go-to phrase for every contrarian teenager on Reddit who’s made New Atheism their entire personality and believes they’re one smart-ass internet quip away from becoming the next Sam Harris or Christopher Hitchens. However, it’s also a favored refuge of liberal Christians who imagine themselves perfectly capable of understanding Marxism without having ever read a single thing that Marx wrote, a skill that would have served me very well in grad school. Yet, as with most things carelessly pulled out of context, this quote does Marx a great disservice without deeper interrogation. You see, it oversimplifies his analysis of religion and misses the existential significance of his critique: Marx wasn’t wagging a self-righteous finger at faith—he was diagnosing a social dysfunction that lingers in the world to this day.

“God is man, man is God.”

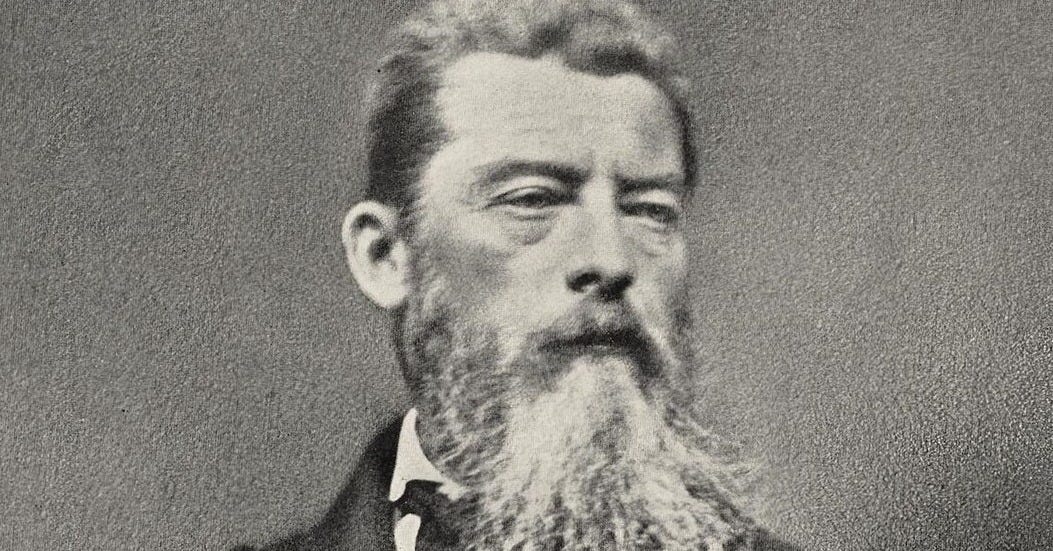

To understand Marx’s critique, we must first discuss Ludwig Feuerbach, a German philosopher whose work greatly impressed Marx. In The Essence of Christianity, Feuerbach endeavored to demonstrate the human origins of religion, asserting that the core doctrines of Christianity contained logical inconsistencies that revealed their terrestrial, rather than transcendent, origins. As such, He argued that religion is, fundamentally, a by-product of human psychology. In other words, when humans imagine God, they’re really just imagining an inflated, idealized version of themselves and the attributes they most wish to possess. Feuerbach’s radical claim was that humanity creates God in its own image—not the other way around. This can be described as “anthropological materialism.” He wrote,

Religion is the relation of man to his own nature—therein lies its truth and its power of moral amelioration; but to his nature not recognized as his own, but regarded as another nature, separate, nay, contradistinguished from his own: herein lies its untruth, its limitation, its contradiction to reason and morality…. [W]hen religion becomes theology, the originally involuntary and harmless separation of God from man becomes an intentional, excogitated separation.

God, accordingly, is a coping mechanism designed to help struggling humans confront life’s many vicissitudes. But, Feuerbach claimed, this creates a problem: by attributing the highest manifestations of love, power, and wisdom to God, we fail to recognize and cultivate these qualities, seeing ourselves as flawed and dependent while God embodies perfection. This process of projection, present in both polytheistic and monotheistic religions, ultimately leads to alienation, the state of being estranged from our own human capabilities. Feuerbach criticized theology, very specifically, for solidifying this separation, creating an artificial chasm that calls upon us to surrender our capacity for reasoning and autonomy.

Theology, on this view, establishes a rigid, hierarchical relationship between God and humanity, where God is positioned as an absolute, all-knowing authority, and humans are relegated to a state of intellectual dependency. This dependency is particularly evident in the concept of revelation, which, in Feuerbach’s view, implies that humans are incapable of independently grasping divine truth. Instead, they must rely on God’s unmediated disclosure, a process that effectively negates the capacity for human reason and promotes intellectual impotence. By accepting revelation, humans forsake their ability to critically evaluate the nature of reality. They become passive recipients of divine pronouncements, rather than active participants in the search for truth, beauty, and goodness. Furthermore, Feuerbach believed that this reliance on external authority extends beyond religious dogma. It permeates social and political structures, where individuals are conditioned to accept hierarchical power dynamics without question. By undermining human reason and autonomy, theology creates a society of dependent subjects, rather than independent, self-determining individuals.

Feuerbach, You Ignorant Slut…

Marx, in his Theses on Feuerbach, agreed that religion is a human creation but rejected Feuerbach’s philosophical approach, which he deemed excessively theoretical and detached from the realities of human existence. Additionally, he critiqued Feuerbach’s analysis of religious alienation, claiming that it failed to grasp the inherently social and practical nature of human existence. Marx insisted that human essence is not an abstract concept, but rather an ensemble of social relations, a network of connections forged through historical processes. He saw religious behavior itself as a social activity, a product of these complex human interactions. In his words,

Feuerbach, consequently, does not see that the “religious sentiment” is itself a social product, and that the abstract individual whom he analyses belongs to a particular form of society.

He thus dismissed the philosophical tendency to ignore practical activity as an area of investigation, advocating instead for a “New Materialism” that aimed not merely to describe reality but to improve it. Religion, Marx says, arises from real material conditions, especially the suffering and alienation caused by unjust economic systems. When people turn to religion, they’re seeking comfort, meaning, and hope in a world that often denies them those things. This is to say that religion, like most everything of existential significance in human life, is a political issue. Nothing, not even the interior life of faith, is immune to the pressure of the sociopolitical frameworks we live and die under.

For Marx, alienation is the key to understanding why religion has such a hold on the public consciousness. Alienation happens when people feel disconnected from their own humanity—from their labor, their creativity, and even their fellow human beings. In a capitalist system, Marx argued, people are reduced to commodities, valued only for what they produce, not for who they are. Religion, then, is a response to this alienation. It offers an idealized version of the world—a promise of justice, happiness, and fulfillment in the afterlife—that stands in contrast to the harsh realities of life under capitalism. But here’s the downside: religion, by its very nature, turns this hope outward, away from the world we live in. It encourages people to focus on an ideal realm rather than working to change the material conditions of this one. In Marx’s view, this makes religion a kind of double-edged sword: it offers comfort but at the likely cost of ignoring, and even perpetuating, the systems that cause suffering in the first place.

Opium des Volkes

This brings us to Marx’s famous remarks about religion. At first glance, it sounds harsh—it’s as if Marx is suggesting that prayer is comparable to a line of cocaine. For what it’s worth, I would probably still be a theist if I could get absolutely blasted by simply saying “now I lay me down to sleep.” But we need a little historical context to unpack Marx’s meaning, here. In Marx’s time, opium wasn’t just associated with addiction—it was also a very common painkiller. Marx is arguing that religion functions as a balm for the pain and suffering of existence, especially for those who feel powerless in the face of institutional exploitation. However, while religion soothes that pain, it doesn’t cure the underlying social disease. For Marx, religion merely addresses the symptoms of a sick society without tackling its root causes—namely, the material conditions that make people feel alienated in the first place. In this sense, Marx isn’t critical of religion because he thinks belief in “God” is an activity reserved for the dumb and uninformed. His criticism of religion acts as an attempt to address the real, human suffering that originally leads people to seek solace in faith.

Marx’s critique of religion is rooted in his deep concern for human flourishing. He doesn’t dismiss the need for hope, meaning, or social connection—the very goods religious institutions often provide. Instead, he argues that these needs can only be truly fulfilled by transforming the material conditions of life. For Marx, this transformation isn’t about rejecting religion outright—it’s about moving beyond it. In this sense, Marx’s critique can be seen as deeply humanistic. He’s not saying that faith is inherently bad—he’s saying that people deserve a world where they don’t have to rely on faith alone to find comfort or justice. Marx wants a world where the ideals that religion points to—community, love, equality—can be realized in the here and now, through human action. Moreover, Marx’s critique of religion isn’t just an intellectual exercise—it’s a call to action. He challenges us to look at the world not as it’s promised to be, but as it is, and to ask: What can we do to make life better, concretely? Whether you agree with Marx or not, his analysis forces us to think critically about the relationship between faith, suffering, and social change.

Why Does This Even Matter?

My intention here is not to undermine anyone’s faith, nor to suggest, as Marx did, that religious impulses are solely products of material deprivation. Our transcultural longing for self-transcendence and our routine engagement with fundamentally religious questions are enduring aspects of human existence, a point Paul Tillich effectively critiqued Marx on in The Socialist Decision. Tillich recognized that our concern for the “ultimate” wouldn’t simply vanish in a different economic system. However, while acknowledging the complexity of religion and it’s origins, particularly from scientific and evolutionary perspectives that reveal a confluence of cognitive and social factors, we must recognize that material realities exert a profound influence on how religious tendencies manifest in society and shape our politics.

Take, for instance, the ascendance of abortion as a pivotal religious issue in late 20th-century America. Though often presented as a matter of pure theological conviction, this movement was profoundly influenced by underlying material realities. Economic anxieties, coupled with strategic political mobilization, fostered a fervent desire for clearly defined moral boundaries and a sense of social order. The anxieties generated by rapid social change, particularly concerning evolving gender roles, were effectively channeled into the anti-abortion movement. Here, we can clearly see the way that material conditions can easily mold and amplify “religious” convictions, culminating in policies that have immense, and often detrimental, consequences. In this case, women and children are hurt as evidenced by the fact that newly enacted abortion bans have broadly led to increased female mortality and a rise in infant deaths across the southern U.S. The singular focus on abortion as a purely religious concern has frequently obscured the complex economic circumstances that lead women to seek the procedure, revealing the intricate and often insidious interplay between material realities and religious worldviews, and how these forces can be exploited to justify nefarious political action.

Furthermore, it’s crucial to acknowledge that economic insecurity can significantly exacerbate underlying authoritarian tendencies, a phenomenon supported by findings in cognitive science. When individuals feel economically vulnerable, they often seek strong, decisive leadership and clear, rigid social structures. This inclination is made worse by the allure of certainty inherent to more conservative theological worldviews. Sometimes, the ambiguity and complexity of modern life can be overwhelming. Religious doctrines that offer absolute truths, clear moral codes, and a sense of divine order provide an escape from this uncertainty. The promise of a fixed, hierarchical structure, where every individual has a defined place and purpose, may prove particularly appealing when the world feels too unpredictable. And this longing for certainty is precisely what authoritarian leaders and rigid religious ideologies exploit. Consider what happened in the Weimar Republic, a topic I’ve addressed at length in other posts. Hitler’s rise to power was not a sudden event, but a slow process of exploiting the insecurity felt by German citizens struggling under the duress of economic hardship. He capitalized on their anxieties, offering simplistic solutions and scapegoats, while simultaneously providing a perverse but enticing sense of cultural pride and civic belonging.

Although the all-too-human impulse toward religious belief is likely far more nuanced than Marx suggested, the specific forms those beliefs take, and how they influence our political and social structures, are undeniably impacted by material realities. When people experience economic insecurity, social instability, and a general sense of existential precarity, their worldviews, including those with metaphysical significance, become susceptible to distortion and manipulation. Thus, while the Marxian analysis of religion may be incomplete, his emphasis on the material forces that shape its expression remains a vital insight for understanding its role in the contemporary world.

So, the next time someone compares religion to opium, remember: Marx wasn’t vilifying religious people. He was asking us to confront the conditions that make escaping to a heavenly paradise so appealing and to imagine a world where those conditions no longer exist. For Marx, religious ideals of justice, community, and love shouldn’t be deferred to the afterlife. They should be realized in the here and now, through human action.

This is an extended version of a video essay I recently uploaded to YouTube, which can be found here:

"Prayer is comparable to a line of cocaine"... I appreciate Marx's approach as opposed to Fuerbach's: he doesn't ignore the human desire for hope, but focuses instead on the material rather than the metaphysical. Thanks for the read!